The members of the Dolphinaria-Free Europe (DFE) coalition offer our heartfelt condolences to those people around the globe who have lost loved ones to the COVID-19 pandemic or have family and friends who are ill. Our thoughts are with those currently suffering from this novel coronavirus or recovering from it.

Understandably, authorities are focused on medical and humanitarian responses. However, those of us working in animal protection continue to monitor captive wildlife care and management. DFE issues this statement to address the ways in which the pandemic has affected, and may continue to affect, captive whales, dolphins and porpoises (cetaceans), the focus of our professional campaigning. There is added urgency to our concerns, as it has emerged that SARS CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19) has the capacity to infect companion animals and captive wildlife, with reports of a positive test for the virus in a captive tiger.

In response to social distancing directives, all dolphinaria in Europe are closed to the public and some have begun furloughing employees. There have been no reported cases to date of SARS CoV-2 in captive marine mammals; we are on the alert for such reports. We note that coronaviruses have been documented in beluga whales and bottlenose dolphins in the past, but these strains are not the same as SARS CoV-2.

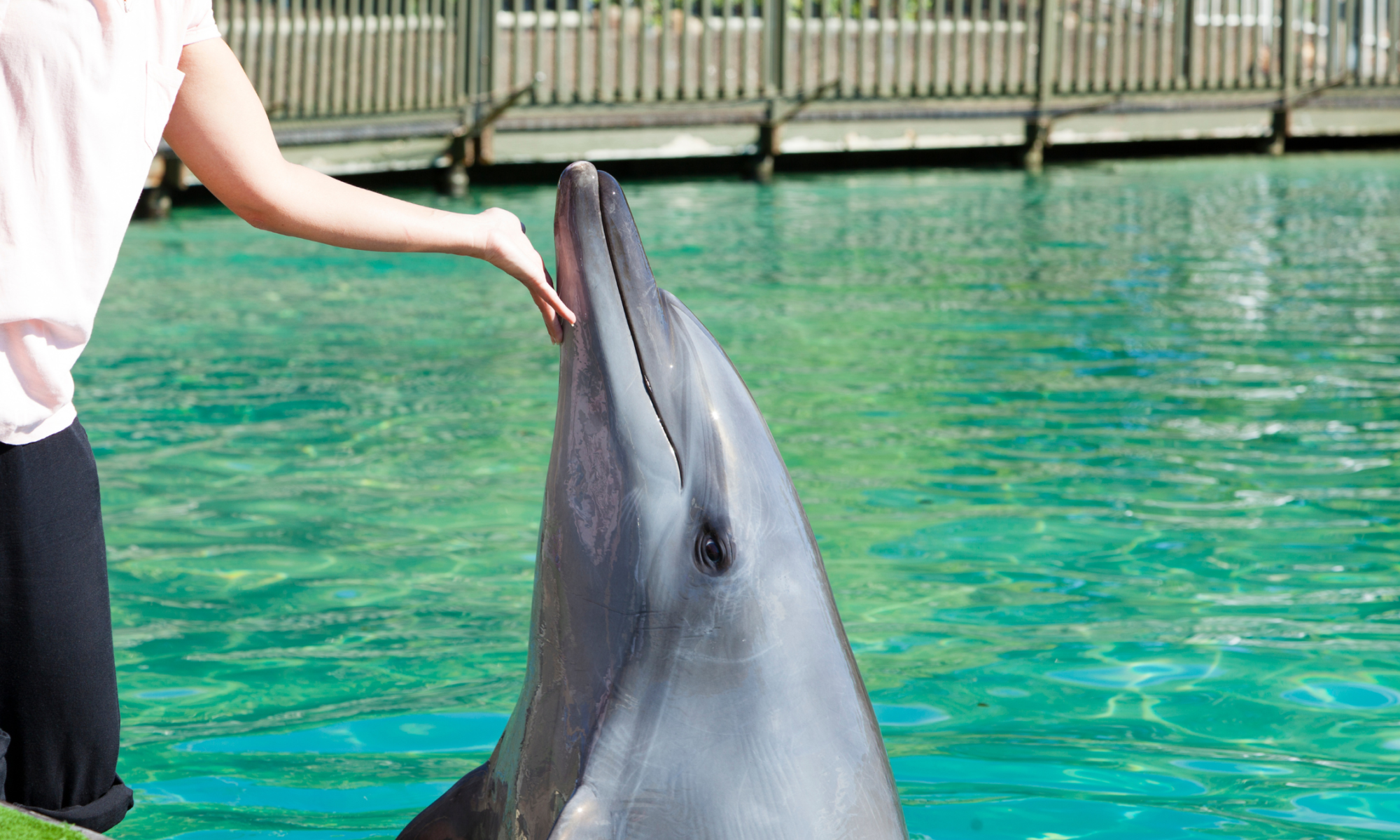

We have serious concerns regarding the impact of temporary staff reductions on the already-compromised welfare of captive cetaceans. With intelligent, social mammals such as cetaceans, reduced interaction with staff can have a severe impact on the mental health of the animals. Captive cetaceans already face abnormal social situations, with individuals held in the same enclosure who are not natural, chosen or sometimes even compatible companions; some are kept in complete isolation. Stress caused by abnormal social groupings can be a serious problem for captive cetaceans. Interactions with trainers are a poor substitute for natural social interactions, but they are a major element of captive husbandry; any reduction in positive trainer interactions will reduce welfare. Veterinary care—particularly routine health monitoring—may also suffer during the pandemic. This becomes a more urgent concern if staff actually contract the virus, given the now-apparent potential for transmission to other mammals. Upper respiratory infections are of particular concern with cetaceans; pneumonia is a common cause of death both in captivity and the wild.

Of equal concern, without income, dolphinaria may find themselves unable to feed their animals, which could lead to the tragic situation of having to consider culling their animals—a term used when otherwise healthy animals are deliberately killed. Culling of captive wildlife was seen during both World Wars and has been employed when disasters or civil unrest disrupt zoo attendance. In Europe, some animals in zoos, such as giraffes, are already occasionally subject to culling, as a questionable means of reducing inbreeding or overcrowding. However, species with individual economic value, such as cetaceans, do not typically face this harsh reality of zoo management. Yet under current circumstances, with facilities closed to the public, this may change, as cetaceans in particular are expensive to maintain. As businesses that attract large gatherings of people remain shuttered, should a dolphinarium no longer be able to afford food and/or veterinary care—or should supply chains begin breaking down and food become difficult to procure— culling cetaceans may become one of very few options remaining for European dolphinaria.[1]

Should culling begin at dolphinaria, which becomes more likely the longer the economy remains in lockdown, this horrific choice may actually be more humane than unavoidable abandonment and starvation. Starvation is a form of acute suffering that no sentient being should ever have to face. DFE maintains that cetaceans in captivity experience inherently compromised welfare, which is chronic and can always be improved if sanctuary or release become options. However, the acute horror of starvation may make death a merciful alternative. This tragic truth underscores the no-win situation for captive wildlife.

With these facts in mind, DFE maintains that the pandemic’s impacts on the global economy highlight how wrong it is for cetaceans to be held in captivity at all. It should now be obvious, if it was not before, how fragile captive cetaceans’ existence is when made utterly dependent on the dead fish fed to them by their trainers. Captive cetaceans are now under the shadow of potential starvation if the global economy remains in crisis mode through what would normally be the tourism high season in Europe. The silver lining in this dark cloud: The global lockdown of most businesses may lead to a cessation—albeit temporary—of captures in the remaining locations where the live cetacean trade for dolphinaria continues to threaten wild populations. For example, it is possible that the drive hunts that begin each year in September in Taiji, Japan, presently the largest source of wild-caught dolphins for display, may not occur this season. In addition, free-ranging cetaceans may now be swimming in an ocean with lower levels of noise and ship traffic and fewer active fishing nets than it has seen in many decades, however short-lived the respite.

Indeed, the pandemic could and should serve as a wake-up call about our treatment of other living beings on this planet. It was the ruthless and cruel live wildlife trade that gave us this pandemic (and others before it). It should therefore be a priority for jurisdictions world-wide to end all wildlife trade, particularly “wet markets” where live wild animals of many species are held in close proximity to people and each other, before being slaughtered and sold as food or for “traditional” medicines. Regardless of cultural norms, this trade is killing people world-wide, subjecting millions of individual animals to unimaginable cruelty and threatening far too many exploited species with extinction; ending it is the only rational option now.

In addition, DFE repeats its ongoing request to European authorities to phase out the captive display of cetaceans. These wide-ranging species are functional and competent in their own ecosystems; they do not need human care. When they are given over to it, through capture or captive breeding, they may die en masse simply because our artificial constructs, including our economy and our international diplomatic relations, temporarily fail. If dolphinaria abandon their animals as a result of this pandemic, or cull them even for mercy’s sake, then they should not be allowed to “restock” their exhibits, from the wild or through captive breeding. Our entertainment and recreation—the primary purposes of cetacean exhibits (most of which include performances and/or swimming encounters), regardless of any secondary research or conservation they may conduct—do not justify the acute suffering or death captive cetaceans risk when money for their care runs short.

Countries have already begun to reconsider their relationship with captive cetaceans, enacting laws and changing policies to limit or end their display. Society generally needs to stop thinking other beings on this planet need us. They not only do not need us, they fare far better without us—witness how many urban areas are being revisited by wildlife not seen in decades because people and vehicles are at record low levels on the streets of cities and towns during the lockdown. The same is likely true of waterways where beach-goers and ship and boat traffic have declined. When it comes to captive wildlife, including cetaceans, we must not return to “business as usual” when the pandemic is over and the economy reopens. Tourism must move beyond commodifying wildlife, ending an ongoing and inescapable cycle where animals are abandoned when economic times get tough but exploited anew when good times come again. It would be yet another tragedy if we miss this opportunity—however devastating its origin—to break the cycle and change the way we relate to wildlife for the better.

DFE will continue to monitor the impact of the pandemic on dolphinaria and the wildlife in their care and respond as needed. Once again, our members’ thoughts are with those suffering during this difficult time.

[1] For sea pen facilities, none of which exist in Europe, release may be an option, but cetaceans who have not been rehabilitated would be unlikely to survive a release where they are expected to fend for themselves in unfamiliar habitat.